The fifth Rebbe of Lubavitch, Rabbi Sholom Dov Ber, was once talking with one of his prominent disciples, a successful diamond merchant named Reb Monia Mosenson. This individual expressed bewilderment that the Rebbe devoted an inordinate amount of time to simple folk who seemed rather unremarkable, ordinary.

"Rebbe, with all due respect," Monia asked, "why do you spend so much time with the commoners? They're nice people, but hardly worthy of the investment of this much of the Rebbe's time and attention. I can't imagine they're asking any profound Talmudic questions or engaging in deep philosophical discussions."

The Rebbe thought for a moment, then turned to Monia and asked, "Do you happen to have any of your merchandise with you?" Monia said, "As a matter a fact, I do" as he opened his pouch and spread some of his wares on the table. He selected a single gem and lifted it up for the Rebbe to see. "Look at that color and clarity. Perfection! A beauty, isn't it?"

The Rebbe was not impressed. "Frankly, I don't see it," he said. "As a matter of fact, that one seems rather ordinary to me. I find this bigger and shinier one far more impressive."

Somewhat disappointed, Monia smiled and said respectfully, "Rebbe, one has to be a 'maven', an expert, on a diamond in order to appreciate its true value."

"Ah, quite correct, Monia" replied the Rebbe. "And one must also be a 'maven' on a soul, in order to appreciate its true value. What you see in those 'ordinary' folk is not quite the same as what I see" (1).

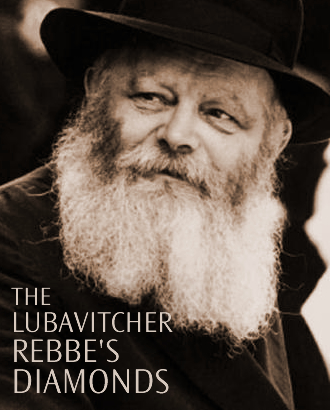

It is this perspective that animated the approach of the seventh Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson. What he saw in people is not quite the same as what most of us see. How then was he able to invigorate and motivate his followers to come around to his way of seeing things - inspiring them to branch out and open thousands of educational institutions, humanitarian projects and outreach centers across the globe - sparking one of the greatest renaissances in Jewish history?

Perhaps an exchange we find in the Talmud will offer some insight. In one of the Tractates dealing with marriage, the Talmud records a fascinating debate between the great schools of Hillel and Shammai. "How is one to praise a bride at her wedding?" was the question on the floor of the study hall (2).

The School of Hillel held that, regardless of what one observes, one should always say, "The bride is beautiful and gracious." In other words, on her wedding day, a bride must be made to feel like the most beautiful woman alive.

The School of Shammai, on the other hand, maintained that you can only call it as you see it. After all, "distance yourself from a lie" (3) is a fundamental Torah principle. Falsehood is anathema to Judaism. Thus, says Shammai, if she is beautiful, talk of her beauty. If she has nice eyes, talk about her eyes. If she has virtue, talk of her virtue. But if you see nothing worthy of praise, then it's best to remain silent rather than offer untrue platitudes (4).

While Hillel's approach certainly seems more sensitive and "politically correct," his opinion is problematic. After all, Shammai demands honesty and truth. Does Hillel discount the importance of speaking the truth?

The answer is that Hillel is not asking you to lie - not at all (5). What he is saying is that you are at a wedding in which this groom is marrying this bride. To him, this woman is the most beautiful in the world. To him, she is the greatest woman in the world. So, says Hillel, when you're at a wedding, respect this man's affection and taste. Find a way to see the bride the way her husband does. Just as he sees her beauty and proclaims it as such, find a way to merge his view with your own -see what he sees - and come from that truth.

Throughout scripture, we find that the relationship between G-d and the Jewish people is referred to as a marriage (6). The Jews met G-d in a desert where they first pledged their love. The event at Sinai was the wedding where G-d married the Children of Israel, joined His fate to theirs and entered a covenant of mutual loyalty. This was not only a marriage with the people, collectively, but with each individual Jew, for all eternity.

From the Rebbe's perspective (7), when you gaze at a fellow Jew, you are seeing someone whom G-d selected as His bride. To G-d, this Jew is the most beautiful person in the world. Likewise, when you look at a Jew, he would say, view the person from G-d's perspective.

The Rebbe was a great defender of the Jewish people when many others were critical, sometimes rightfully so. He sang the melody of Hillel and was able to see the good within the not-yet-good. For over 40 years of leadership, one note infused all of his talks: the love, generosity of spirit, even awe for this people who, though much afflicted, never gave up its faith. This remarkable people who, after the Holocaust, collectively rebuilt Jewish life throughout the world; this exceptional people who, despite the weight of modernity and post-modernity, still identified as Jews, came to the aid of other Jews in need wherever they are, who carried underneath the surface of their lives a shimmering ember of identity which - with but a gentle touch - could be fanned into a flame.

The following episode (8) movingly illustrates the Rebbe's "Hillel-like" approach:

For those seeking to meet the Lubavitcher Rebbe, one opportunity to do so was at the conclusion of the Chassidic gatherings (farbrengens) the Rebbe held at the close of every festival. Following the Havdalah ceremony marking the holiday's end, the Rebbe would continue to refill his ceremonial cup and pour a bit of the wine into the cup of each participant who passed before him. This practice, referred to as "kos shel berachah" (cup of blessing), enabled the thousands on hand to share an auspicious moment with the Rebbe. Long lines crisscrossed the large synagogue on Eastern Parkway and spilled out into the street. It was often close to dawn when the last in line received his splash of wine from the Rebbe's cup and a brief blessing from the Rebbe.

One such night, an unlikely visitor was standing on line for kos shel berachah, the secular writer and publicist, Natan Yellin-Mur.

Born in Vilna to observant parents Natan was educated in that city's world-renowned Jewish academies (yeshivot). As a young man, however, Natan abandoned the beliefs and practices of Judaism in favor of secular Zionism. He became a leading Zionist activist, finally making his way to the Holy Land. There he joined Lechi ("The Stern Gang"), the most combative of the Zionist groups fighting for an independent Jewish state.

After the establishment of the state in 1948, as mundane politics replaced the ideological fervor of the pre-independence years, Natan became disillusioned with the cause for which he had fought with such intensity. He turned fiercely anti-Zionist. An eloquent writer, he regularly published articles defaming everything Jewish, and particularly the Jewish state and its policies.

Natan was on line for kos shel berachah that night because of his acquaintance with the late Gershon Jacobson, editor of the New York-based Yiddish language newspaper, The Algemeiner Journal. Gershon Jacobson was a religious Jew and a Lubavitcher Chassid. He was certainly pro-Israel and supportive of Judaism; but Jacobson also believed in journalistic pluralism, and, to the consternation of many of his readers, he invited the self-proclaimed atheist and anti-Zionist to write for the Algemeiner, often publishing the venomously anti-Israel and anti-Jewish articles the writer sent in. When Gershon suggested to Natan that he meet the Rebbe, the writer accepted the invitation.

As the two men approached the Rebbe, Mr. Jacobson introduced his guest. The Rebbe turned to Natan, smiled broadly, and said: "I've read your articles."

Natan's idea of a Chassidic Rebbe did not prepare him for a person who reads newspapers, much less articles such as his own. But what surprised him even more was what followed:

"When G-d blesses someone with a talent such as yours," the Rebbe continued, "One must utilize it to the fullest. This is a divine calling, and an immense responsibility. It is your G-d-given power and duty to make full use of your capacity to reach out to others and influence them with your writing."

Thinking that the Rebbe was mistaking him for someone else, Natan asked: "Does the Rebbe agree with what I write?"

The Rebbe replied: "One need not agree with everything one reads." The Rebbe then shifted the conversation back to his essential point. "What is most important is that one utilizes one's G-d-given talents. When one does so, one will ultimately arrive at the truth."

Before the grateful writer could adjust to Rebbe's surprising approach, the Rebbe's next words struck a place in his heart he'd long thought to have been silenced forever. "Tell me," said the Rebbe in a gentle yet firm tone, "What is happening in regard to your observance of Torah and mitzvot?"

Not wanting to lie to the Rebbe by pretending to be observant, nor wishing to offend him with his anti-religiosity, Natan replied: "A Jew contemplates."

"But in Yiddishkeit," countered the Rebbe, quoting the Talmudic maxim familiar to Natan from his yeshiva years, "it's most important to do. 'The primary thing is the deed.'"

Slyly, Natan responded, "At least with me it's like in the story with the Berditchever."

Natan was referring to the story told of Rabbi Levi Yitzchak of Berditchev's encounter with a Jew who was smoking a in the street on Shabbat. Rabbi Levi Yitzchak, famed for his inability to see anything negative in a fellow Jew and his persistent advocacy on behalf of his people, said to the man, "My friend, surely you have forgotten that it is Shabbat today."

"No," said the man, "I know what day it is."

"Then surely you have forgotten that smoking is forbidden on Shabbat."

"No," said the man, "I know it is forbidden."

"Then surely, you must have been thinking about something else when you lit the cigarette."

"No," the man replied, "I knew what I was doing." At this, Levi Yitzhak turned his eyes upward to heaven and said, "Sovereign of the universe, how precious are Your people, Israel. Even when he transgresses, he still cannot tell a lie!"

There are many stories told of Rabbi Levi Yitzchak of Berditchev, so Natan was about to tell the Rebbe the story to which he was referring. But before he could get out another word, the Rebbe rejoined: "The difference is that the Berditchever said this in defense of another person, while you are saying it in defense of yourself..."

With that, the meeting came to a close. The Rebbe poured some wine into Natan's cup, blessed him, and turned to the next in line.

Several months later, Natan was sadly diagnosed with terminal cancer. The doctors gave him but a few months to live. Shortly before his death, he sent a sealed envelope to Gershon Jacobson, with a note stating that it contained an article which he wished to be published posthumously.

Gershon complied, and following Natan's death, the article was printed in The Algemeiner Journal. "My dear reader," Natan had written. "As you read this article, I am standing before the heavenly court being judged for all the actions I took and the choices I made in the course of my life. No doubt, I will be judged for living a life totally antithetical to anything Jewish. In fact, I have severe doubts that I will even be allowed to speak in my defense. This is why I asked your editor to print this now, as I stand before the heavenly court, in the hope that what is being read and discussed at this moment on earth will attract the attention of the Supernal Judge. For I do have one merit I wish to present to the court in the face of all my failings and transgressions."

At this point, Natan related his exchange with the Rebbe at kos shel berachah and concluded, "The Rebbe said to me that I have a G-d-given talent, and that it is my sacred duty to utilize it to influence others. This I did to the best of my ability, however misguidedly. This is the only merit I can claim; may it lighten the destiny of my soul...."

This story encapsulates the Rebbe's approach. He saw every Jew as a beautiful bride and extolled her as beautiful and gracious. He saw in every Jew's heart a spark of heavenly fire and marvelous potential.

To the Rebbe, ahavat yisrael, love of every Jew, was not a refusal to see deficiencies, but an unequivocal love regardless of his or her spiritual state. He loved and taught that G-d loves - as a father loves his children - regardless of who and what they are. And he believed that through this love, we would be able to help others actualize their deepest potential.

It is said of Michelangelo that when he carved his remarkable statue of David he was conscious not of creating it but of uncovering it. He could already see a David there, present in the uncured rock. It takes a similar largeness of spirit to see, in a profoundly disaffiliated Jew, faith and sanctity when to all appearances he has neither of these things. This is what the Rebbe attempted to do with Natan Yellin-Mur as well as with countless others.

Today, in many works of post-Holocaust Jewish theology you will find the same question. What unites the Jewish world now, with all our disagreements and denominational fragmentation? Their answer is usually this: What links the Jewish people today is memories of the Holocaust, fears of anti-semitism, and its new, virulent form which questions Jewish existence in Israel. In short, what unites us as a people is that many gentiles hate us.

The Rebbe taught the opposite. What unites us is not that gentiles hate us, but that G-d loves us; every one of us is touched by the Divine presence and together we can we can build a world of righteousness worthy of being a home for G-d. Surely that message is much more empowering and inspirational than the alternative.

Where others might have seen gloom and limited worth, the Rebbe saw the priceless gem that is the soul. Moreover, he sought to make us into experts, that we might see it too. So that when we looked at our fellow, we would not only see him for who he is today, but for who he can become; that we would spare no effort or energy in reaching out to another Jew, revealing that inner diamond - nurturing it, polishing it, cherishing it.

Indeed, within every Jewish "bride" there is something unique, yet something that is all too easily eclipsed, and can only grow when exposed to someone else's recognition and praise. To see the virtue in others and let them see themselves in the reflection of our regard is to help someone grow to their potential. In the words of the Talmud, "Causing others to do good is even superior to doing good oneself (9)." To help others reach their potential is to give birth to creativity in someone else's soul. This is not done by criticism and negativity, but by searching for the good in others, complimenting it, helping them see it, own it, live it.

The idea that each of us has a fixed amount of holiness, virtue and faith is incorrect. Each of us have holiness which can lie dormant until someone awakens it. We can all achieve spiritual heights which we never thought ourselves capable. All it takes is for us to meet someone who believes in us more than we believe in ourselves. Such people change lives.

This is what the Lubavitcher Rebbe did for Natan Yellin-Mur and so many others. This is what he empowered us to do. How urgently we need this message today. May this legacy continue to inspire us, as we seek together to mend the Jewish world and bring redemption to humanity.

- Sefer Hasichos 5705 (Talks of Rabbi Yosef Yitzchok of Lubavitch, 1944-45), p. 40.

- Ketuvot 16b-17a.

- Exodus 23: 7.

- Rashi holds, that according to Bet Shammai we should sing to each bride "relative to her beauty and stature". Tosafos maintain that if she has a blemish we should be silent and not sing her praises at all, alternatively, Tosafos, offers a second opinion -- We should sing only of her pleasant attributes, the latter interpretation is like Rashi. See Ritva for an alternative.

- See Maharsha.

- One of the most moving and revolutionary descriptions of faith are the words G-d says to Israel: "I will betroth you to me forever; I will betroth you in righteousness and justice, in love and compassion. I will betroth you in faithfulness, and you will know the Lord." (Hosea 2: 16-22) The Torah saw the ideal relationship between G-d and us in terms of a loving relationship between husband and wife.

- see Likkutei Sichos vol. 16 pp. 313-321.

- Adapted from Week in Review VHH, by Yanky Tauber.

- Jerusalem Talmud Baba Batra 9a.